Tensor Structure and Ownership

In rust, strict rules are applied to ownership and lifetime (related to concept of view). It is important to know how data (memory of large bulk of floats) is stored and handled, and whether a variable owns or references these data.

As a tensor crate, we also hope to have some unified API functions or operations, that can handle computations both on owned and referenced tensors.

In vulgar words, numpy is convenient, and one may hope to code pythonicly in rust.

In this section, we will try to show how RSTSR constructs tensor struct and different ownerships of tensors works.

1. Tensor Structure

RSTSR tensor learns a lot from rust crate ndarray.

Structure and usage of RSTSR's TensorBase is similar to ndarray's ArrayBase; however, they are different in many key points.

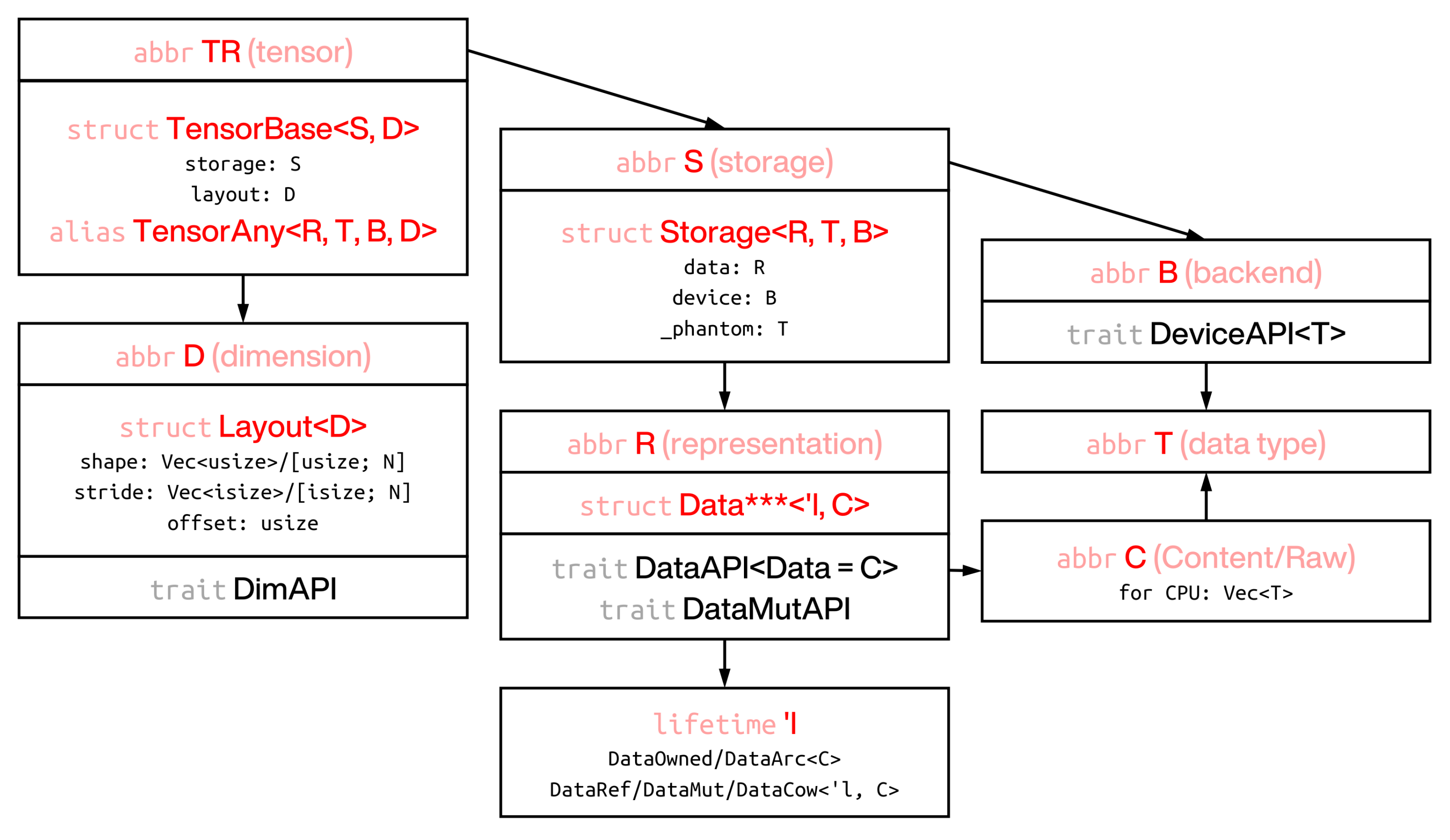

- Tensor is composed by

storage(how data is stored in memory bulk) andlayout(how tensor is represented). - Layout is composed by

shape(shape of tensor),stride(how each value is accessed from memory bulk), andoffset(where the tensor starts)1. - Storage is composed by

data(data with lifetime) anddevice(computation and storage backend)2. - Data is combination of the actual memory storage with the lifetime annotation to it.

Currently, 5 ownership types are supported. The first two (owned and referenced) are the most important3.

- Owned (

Tensor<T, B, D>) - Referenced (

TensorView<'l, T, B, D>orTensorRef<'l, T, B, D>) - Mutablly referenced (

TensorViewMut<'l, T, B, D>orTensorMut<'l, T, B, D>) - Clone on write (not mutable enum of owned and referenced,

TensorCow<'l, T, B, D>) - Atomic reference counted (safe in threading,

TensorArc<T, B, D>)

- Owned (

- The actual memory bulk will be stored as

Vec<T>if CPU device. For other devices, this can be configured by trait typeDeviceRawAPI<T>::Raw4.

Default generic types is applied to some structs or alias. For example, if DeviceFaer is the default device (which is enabled by crate feature faer_as_default), then

let a: Tensor<f64> = rt::zeros([3, 4]);

// this refers to Tensor<f64, DeviceFaer, IxD>

// default device: DeviceFaer (rayon parallel with Faer matmul, requires feature `faer_as_default`)

// default dimensionality: IxD (dynamic dimension)

2. Ownership Conversion

2.1 Tensor to tensor ownership conversion

Different ownerships can be converted to each other. However, some conversion functions may have some costs (explicit memory copy).

viewgivesTensorView<'l, T, B, D>.- This function will always not perform memory copy (of tensor data) in any cases. For this part, it is virtually zero-cost.

- It will still perform clone of tensor layout, so still some overhead occurs. For large tensor, it is cheap.

view_mutgivesTensorMut<'l, T, B, D>.- In rust, either many const references or only one mutable reference is allowed.

This is also true for

TensorViewas const reference andTensorMutas mutable reference.

- In rust, either many const references or only one mutable reference is allowed.

This is also true for

into_owned_keep_layoutgivesTensor<T, B, D>.- For

Tensor, this is free of memory copy; - For

TensorViewandTensorMut, this requires explicit memory copy. Note that it is usually more proper to useinto_ownedin this case. - For

TensorArc, this is free of memory copy, but please note that it may panic when strong reference count is not exactly one. You may usetensor.data().strong_count()to check strong reference count. - For

TensorCow, if it is owned (DataCow::Owned), then it is free of memory copy; if it is reference (DataCow::Ref), then it requires explicit memory copy.

- For

into_ownedalso givesTensor<T, B, D>.- This function is different to

into_owned_keep_layout, in thatinto_ownedonly not copy memory when layout of tensor covers all memory (size of memory bulk is the same to size of tensor layout). Callinginto_ownedto any non-trivial slicing of tensor will incur memory copy. - Also note that, if you just want to shrink the memory to a slice of tensor, using

into_ownedis more appropriate. - For

TensorViewandTensorMut, usinginto_ownedwill copy less memoryinto_owned_keep_layout. Sointo_ownedis preferrable for tensor views.

- This function is different to

into_cowgivesTensorCow<'l, T, B, D>.- This function does not have any cost.

into_shared_keep_layoutandinto_sharedgivesTensorArc<'l, T, B, D>. This is similar tointo_owned_keep_layoutandinto_owned.

An example for tensor ownership conversion follows:

// generate 1-D owned tensor

let tensor = rt::arange(12);

let ptr_1 = tensor.as_ptr();

// this will give owned tensor with 2-D shape

// since previous tensor is contiguous, this will not copy memory

let mut tensor = tensor.into_shape([3, 4]);

tensor += 1; // inplace operation

let ptr_2 = tensor.as_ptr();

// until now, memory has not been copied

assert_eq!(ptr_1, ptr_2);

// convert to view

let tensor_view = tensor.view();

// from view to owned tensor

let tensor = tensor_view.into_owned();

let ptr_3 = tensor.as_ptr();

// now memory has been copied

assert_ne!(ptr_2, ptr_3);

2.2 Tensor and Vec<T> conversion

We have already touched some array creation functions in previous section. Here we will cover more on this topic.

Converting between Tensor and Vec<T> or &[T] can be useful if

- transfer data to other objects (such as candle, ndarray, nalgebra),

- need pointer to perform FFI operations (such as BLAS, Lapack),

- export data to be further serialized.

There are some useful functions to perform Tensor to Vec<T>:

to_vec(): copy 1-D tensor to vector, requires memory copy;into_vec(): move 1-D tensor to vector if memory is contiguous; otherwise copy 1-D tensor to vector.

We do not provide functions that give &[T] or &mut [T].

However, we provide function as_ptr() and as_mut_ptr(), giving the pointer of the first element.

Please note the above mentioned utilities only works in CPU.

For other devices (will implemented in future), you may wish to first convert tensor into CPU, then perform Tensor to Vec<T> conversion.

As an example, we compute matrix-vector multiplication and report Vec<f64>:

// generate *dynamic* 2-D tensor (vec![3, 4] is dynamic)

let a = rt::arange(12.0).into_shape(vec![3, 4]);

let b = rt::arange(4.0);

// matrix multiplication (gemv 2-D x 1-D case)

let c = a % b;

println!("{:?}", c);

let ptr_1 = c.as_ptr();

// convert to Vec<f64>

let c = c.into_vec();

let ptr_2 = c.as_ptr();

println!("{:?}", c);

println!("{:?}", core::any::type_name_of_val(&c));

assert_eq!(c, vec![14.0, 38.0, 62.0]);

// memory has been moved and no copy occurs if using `into_vec` instead of `to_vec`

assert_eq!(ptr_1, ptr_2);

The functions as_ptr() and as_mut_ptr() return pointers to the first element of the tensor's memory; however, it should be noted that the tensor pointed to by these pointers is not necessarily contiguous. RSTSR does not check whether the tensor is contiguous when providing these pointers.

let a = rt::arange(12.0).into_shape([3, 4]);

let a_ptr = a.as_ptr();

println!("{:}", a);

// output: [[ 0 1 2 3]

// [ 4 5 6 7]

// [ 8 9 10 11]]

// please note that b is not contiguous

// be careful if you want to use `as_ptr` on non-contiguous tensor

let b = a.i(slice!(1, None, -1));

let b_ptr = b.as_ptr();

println!("{:}", b);

// output: [[ 4 5 6 7]

// [ 0 1 2 3]]

println!("{:}", unsafe { a_ptr.offset_from(b_ptr) });

// output: -4

2.3 Tensor and scalar conversion

RSTSR do not provide method that directly convert T to 0-D tensor Tensor<T, Ix0, B>.

For convertion of 0-D tensor Tensor<T, Ix0, B> to T, we provide to_scalar function.

As an example, we compute innerdot and report float result:

// a: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

let a = rt::arange(5.0);

// b: [4, 3, 2, 1, 0]

let b = rt::arange(5.0);

let b = b.slice(slice!(None, None, -1)); // or b.flip(0)

// matrix multiplication (dot product for 1-D case)

let c = a % b;

// to now, it is still 0-D tensor

println!("{:?}", c);

// convert to scalar

let c = c.to_scalar();

println!("{:?}", c);

assert_eq!(c, 10.0);

3. Dimension Conversion

RSTSR provides fixed dimension and dynamic dimension tensors. Dimensions can be converted by into_dim::<D>() or into_dyn.

// fixed dimension

let a = rt::arange(12).into_shape([3, 4]);

println!("{:?}", a);

// output: 2-Dim (dyn), contiguous: Cc

// convert to dynamic dimension

let a = a.into_dim::<IxD>(); // or a.into_dyn();

println!("{:?}", a);

// output: 2-Dim (dyn), contiguous: Cc

// convert to fixed dimension again

let a = a.into_dim::<Ix2>();

println!("{:?}", a);

// output: 2-Dim, contiguous: Cc

We only touched array creation with fixed dimension. To create array with dynamic dimension, use Vec<T> instead of [T; N]:

let a = rt::arange(12).into_shape(vec![3, 4]);

println!("{:?}", a);

// output: 2-Dim (dyn), contiguous: Cc

Fixed dimension will be more efficient than dynamic dimension. However, in many arithmetic computations, depneding on contiguous of tensors, the efficiency difference will not be very notable. Meanwhile, RSTSR provides the dispatch_dim_layout_iter Cargo feature; this ensures that the computational efficiency of dynamic dimensions is comparable to that of fixed dimensions when performing calculations on larger tensors.

Considering that the computational efficiency of dynamic dimensions is generally not significantly lower than that of fixed dimensions, we recommend RSTSR users to actively utilize dynamic dimensions.

For dimensionality, RSTSR uses similar workarounds to rust crate ndarray, which provides only fixed dimension. Fixed dimension means is fixed at compile time for -D tensor. This is different to numpy, which dimension is always dynamic.

RSTSR is very different to rust crates nalgebra and dfdx; these rust crates supports fixed shape and strides.

That is to say, not only dimension is fixed, but also shape and strides are known at compile time.

For small vectors or matrices, fixing shape and strides can usually be compiled to much more efficient assembly code.

For large vectors or matrices, that will depends on types of arithmetic computations;

compiler with -O3 is not omniscient, and in most cases, fixing shape and strides will not benefit more than manual cache, pipeline and multi-threading optimization.

Writing a function with more efficiency is more preferrable than telling compiler the dimensionality of tensor.

RSTSR, by design and motivation, is for scientific computation for medium or large tensors. By concerning benefits and difficulties, we choose not introducing fixed shape and strides. This leaves RSTSR not suitable for tasks that handling small matrices (such as gaming and shading). For some tasks that are sensitive to certain shapes (such as filter shape of CNN in deep learning), RSTSR is suitable for tensor storage, and user may wish to use custom computation functions instead of RSTSR's to perform computation intensive parts.

Footnotes

-

RSTSR is different to ndarray in struct construction. While ndarray stores shape and stride directly in

ArrayBase, in RSTSR shape, stride and offset are stored inLayout<D>. Layout of tensor is meta data of tensor, and it can be detached from data of tensor. ↩ -

This distinguishes RSTSR and ndarray. We hope that RSTSR will become multi-backend framework in future. Currently, we have implemented serial CPU device (

DeviceCpuSerial) and parallel CPU device with Faer matmul (DeviceFaer), showing the possiblity of more demanding heterogeneous programming within framework of RSTSR. ↩ -

In RSTSR, data is stored as variable or its reference, in safe rust. This is different to ndarray, which stores pointer (with offset) and memory data (if owned) or phantom lifetime annotation (if referenced). ↩

-

This distinguishes RSTSR and candle. RSTSR allows external implementation of backends, hopefully allowing easy extending to other kind of devices, similar to burn. RSTSR also allows virtaully all kinds of element types (you can take

rugor evenVec<T>as tensor element, as they implementedClone), similar to ndarray. However, RSTSR will probably not implement autodiff in future, which is drawback compared to candle and burn. ↩